'OKLAHOMA!' - OH WHAT-A-NOT-SO-BEAUTIFUL MORNNG

Friday, April 12, 2019 at 11:03PM

Friday, April 12, 2019 at 11:03PM  Damon Daunno, Rebecca Naomi Jones and Patrick Vaill

Damon Daunno, Rebecca Naomi Jones and Patrick Vaill

HENRY EDWARDS - New York - April 14, 2019

More than 300 productions of Rogers and Hammerstein’s first collaboration, “Oklahoma!,” are staged across America in a typical year and undoubtedly not a single one bares the slightest resemblance to experimental director Daniel Fish’s audacious, radical and radically stripped down interpretation at Broadway’s Circle In The Square Theatre.

R&H’s beloved 76-year-old classic has been viewed habitually as an emphatically tuneful demonstration of American optimism and self-assurance; Fish’s non-MAGA approach reveals the genuinely disturbing side to America’s unrelenting and self-infatuated self-confidence.

"The hope is that it's dark and disturbing and celebratory and happy and all of these things thrown together,” the director says of his production.

Fish introduced his deconstruction at Bard College’s 2015 SummerScape Festival. After a multi-extended and generally acclaimed 2018 mounting at Brooklyn’s St. Ann’s Warehouse, the show staked out a claim on Broadway, beginning on March 19.

The original production held its Main Stem debut on the last day of March 1943 just three months after the United States entered World War II.

R&H set the musical in the Oklahoma Territory in 1906, a year before the poor ranching and farming district achieves statehood. Their romanticized version of the past conjures a close-knit community working together to give birth to a new state.

The team launched the show with one of their greatest anthems, "Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin'.”

“I've got a beautiful feelin' -- everything's goin' my way!" declared the lyric, providing a hefty dose of jubilant medicine to the citizens of an anxious nation at war.

Perceived as a ringing endorsement of American values and the need to defend them, “Oklahoma!” seemed to be sending word that everything was destined to go America’s way.

By the time the show ended its initial five and one-half year Broadway run, it had attracted the largest audience in the history of the American musical theater.

Oklahoman writer Lynn Riggs' 1931 (far from successful) nostalgia-driven Broadway play, "Green Grow the Lilacs" provided the source material for Oscar Hammerstein’s faithful adaptation.

Both the original play and Hammerstein’s book relate the same modest story:

Cowboy Curly McLain (Damon Daunno) wants to take farm girl Laurey Williams (Rebecca Naomi Jones) to the town box social. So does her family’s hired hand, loner Jud Fry (Patrick Vaill).

In a contrasting comedy sub-plot, “girl-who-can’t-say-no” Ado Annie Carnes (Ali Stroker) has to choose between her wide-eyed cowboy suitor Will Parker (James Davis) and unwilling Persian peddler Ali Hakim (Will Brill).

Three (long) hours later, Curly and Laurey are married, Jud is dead, Annie and Will have worked out their differences, and the settlers are all cheerily singing, “Everythin’s goin’ my way.”

I have previously seen two Broadway productions of “Oklahoma!’ (1979 and 2002, directed by Trevor Nunn and subsequently broadcast on PBS starring Hugh Jackman), along with Fred Zinnemann’s 1955 movie version, and I have always had the same reaction.

I emphatically respect “Oklahoma!” and gratefully acknowledge it as perhaps the most influential of all Broadway musicals.

R&H had the genius to embed song and dance so fully into the drama that they become an indispensable part of it, resulting in the first “integrated” musical in theatre history and the first entry in the glorious 25-year Golden Age of the Broadway Musical.

But a musical that revolves around which cowboy will marry which farmer’s daughter has the same effect on me as a double dose of Ambien. It’s a bore.

Darkness has always lurked beneath the show’s vision of a corn-fed, star-spangled Americana. To Fish’s credit, his intimate and contemporized makeover at long last allows the darkness to show through.

Remarkably, his production preserves every line and melody from the original score – with one devastating exception as the show nears its conclusion.

The director's extremist alteration transforms “Oklahoma!” into a suddenly brand new, disturbing, frighteningly contemporary show.

Set designer Laura Jellinek’s environmental-theatre transforms Circle In The Square into a community meeting hall with the audience wrapped around the three-sided playing area and in very close proximity to the actors.

Blond plywood boards are nailed into the theater’s walls and floor, colorful metallic fringe and strings of glittering Christmas lights hang from the ceiling, and guns – lots and lots of guns – are mounted on the side walls and visible from every vantage point. They serve to remind us of the violence in 1906 and regrettably of now. It is as if we were visiting the birthplace of the gun culture.

The stage is virtually empty except for plywood tables along the perimeter, topped with hampers, portable coolers, piles of corn and blood-red Crock-Pots filled with chili. (The chili is served, with corn bread, at intermission – additional proof that we are all members of the same community and we are all in it together.)

In another reinforcement of the communal nature of the event, lighting designer Scott Zielinski’s blazing white house lights remain on for most of the show. The audience and cast see each other freely and as much as we look at them, they look at us.

Arranger Daniel Kruger has reduced the orchestra from the traditional 28 musicians to seven; Nathan Koci conducts the band in a shallow pit cut of the plywood stage.

Kluger’s job was to erase any trace of legendary Broadway arranger Robert Russell Bennett’s original orchestrations.

Bennett literally is the creator of the traditional Broadway sound, and responsible for the massive 8-part chorale near the end of the title song and to extending it to include the famous spelling of the name, Oklahoma.

Kluger left the score’s underlying musical architecture, arrangements and sumptuous harmonies in place, but radically changed the instrumentation, incorporating banjo, pedal steel guitar, and mandolin, but retaining bass, cello, and violin.

The captivating result has a far more authentic turn-of-the-twentieth-century ring minus any Broadway bombast.

Trevor Nunn’s production employed 36 actors; Fish eliminated the chorus and 12 actors do all the heavy lifting.

They are dressed in costume designer Terese Wadden’s casual modern dress, sit at a few tables and on wooden folding chairs on the playing area and often remain onstage Brecht style as the action moves forward.

As originally conceived, romantic leads, soprano Laurey and baritone Curly are classic musical-comedy white-bread types with “legitimate” voices that enable them to sing in operetta mode; less self-aware, less educated subsidiary pair, Will Parker and Ado Annie, perform in a less “cultivated” musical comedy idiom.

Curly is a traditional romantic hero, the most handsome man in the county and blessed with a confident swagger; Laurey is the perfect ingénue — virginal yet possessing an air of knowledge about life.

In a traditional production, Damon Daunno and Rebecca Naomi Jones would never be cast in these roles.

Daunno comes from an Italian-American New Jersey family and his Curly is a mix of bravado, arrogance and silliness.

Jones was raised in Tribeca by an African-American father who worked as a vocal coach for doo-wop and oldies acts, and a Jewish mother. She is a steely-eyed, independent and doing her best to choose between Curley and dour Jud.

Unlike traditional, larger-than-life musical-theatre couples of yore, the duo creates a readily identifiable, life-sized, attractive, sex and contemporary interracial dating couple.

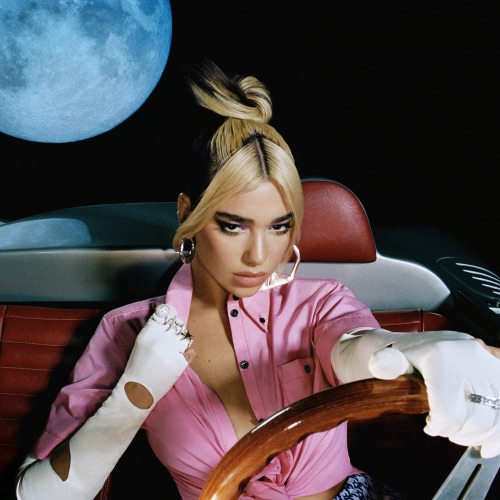

At the age of two, Ali Stroker, the Ado Annie of “Oklahoma!,” was in a car accident that resulted in a spinal cord injury that left her paralyzed from the chest down. Because she is unable to walk, she uses a wheelchair.

Stroker’s Ado Annie is mostly sweet, impulsive, frankly physical and fun loving at a time when the consequences seem remote.

Ali Stroker

Ali Stroker

R&H musicals generally represent the values of a middle-class society with a suppressed id.

Thus "Oklahoma!” deals with Ado Annie’s sexuality by making it a joke. Stroker is hilarious whirling around in her chair unaware of her indiscretions and busy fulfilling them. The approach preserves her status as a fundamentally moral character that is redeemable by the end of the show.

In the world of R&H, the choice between good and evil is always clear-cut, and Judd Fry traditionally qualifies as “evil.” Nobody likes him; he lives a lonely depressive existence in the smokehouse; and his outsider status makes him a danger to the community.

Fish busts the game wide open by electing Patrick Vaill to be the first appealing actor ever to play this role.

Vaill gives a superb performance, rendering a very personal and tender portrayal of someone who is in profound pain with tragic implications.

In the original production, Laurey and Curly are married and everyone rejoices in celebration of the territory's impending statehood ("Oklahoma").

A drunken Jud harasses Laurey by kissing her and punches Curly, and they begin a fist fight. Jud attacks Curly with a knife and Curly dodges, causing Jud to fall on his own knife and Jud soon dies.

The wedding guests hold a makeshift trial for Curly at Aunt Eller's urging as the couple is due to leave for their honeymoon.

In a grave but forgivable dispatching of justice, the judge, Andrew Carnes, declares the verdict: "not guilty!" and in the happiest of endings, Curly and Laurey depart on their honeymoon in the surrey with the fringe on top.

Damon Daunno, Rebecca Naomi Jones

Damon Daunno, Rebecca Naomi Jones

In Fish’s version, Judd kisses Laurey and starts to advance on Curly, who shoots him from several feet away, blood splattering all over the bride and groom’s white clothes.

Dispensing with the rule of law, a decision is made as to whether Curly is a murderer. (He is.) Even though a federal marshal tries to insist on a courthouse trial, he is brushed off, enabling Curly can set out on his honeymoon.

The newlyweds’ clothes are still drenched with blood as the company brings the show to a conclusion with a taste of “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” and a hearty reprise of “Oklahoma!” (“You're doin' fine, Oklahoma! Oklahoma, you're O.K,”).

We are witnessing the birth of the pathological tribalism that currently consumes America - and it is an ironic and disturbing shocker.

O.K. then?

By the time Oklahoma became a state, the Native American tribes in the region lost approximately two-thirds of the land the government had previously given them - a signifiant clue to the greatness of those days gone by.

O,K. now?

Fish says of his revised take: "It makes the community culpable, and I would argue that it probably makes the audience culpable, as well . . . It's an old story, but it's also a story that matters now in terms of issues of community, in terms of violence, in terms of how we create outsiders and in terms of love."

Here is one“Oklahoma!” that is not going to put you to sleep.

The show continues through Jan 2020 at Circle in the Square Theater - For more information and tickets: Click OKLAHOMA

Damon Daunno, Rebecca Naomi Jones and Patrick Vaill Ali Stroker Damon Daunno, Rebecca Naomi Jones Cast

Damon Daunno, Rebecca Naomi Jones and Patrick Vaill Ali Stroker Damon Daunno, Rebecca Naomi Jones Cast

Henry Edwards | Comments Off |

Henry Edwards | Comments Off |