'THE LEHMAN TRILOGY' - THE 167-YEAR RISE AND FALL OF THE FINANCIAL GIANTS

Tuesday, April 16, 2019 at 7:22PM

Tuesday, April 16, 2019 at 7:22PM

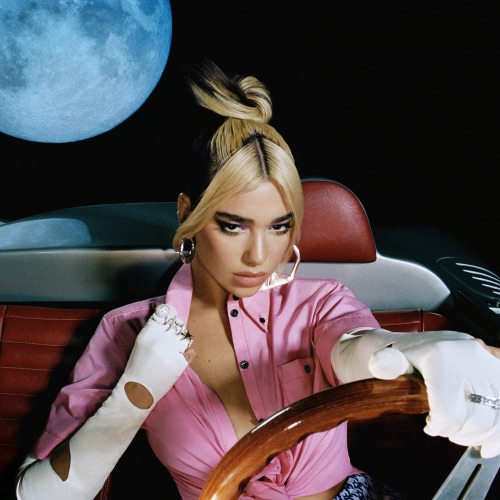

Adam Godley, Simon Russell Beale, Ben Miles

Adam Godley, Simon Russell Beale, Ben Miles

After a critically-acclaimed stint in London’s National Theater, “The Lehman Trilogy” has arrived at the Park Avenue Armory for 33 performances and the brief engagement has turned into the must-see event of the theatre season.

The show – it runs a supersized three hours 30 minutes (three acts and two intermissions) - has been virtually sold out long before opening night. Tickets to the best locations in the vast 1,500-seat Wade Thompson Drill Hall run $450 apiece; StubHub is charging $1,200 to $2,000 for the final performances.

What are audiences paying so much to see?

A program note in the giant-sized program characterizes the play as “the story of Western Capitalism told through a single family.”

How’s that for a grandiose concept?

Three 19th-century Jewish-German immigrant brothers, Henry, Emanuel and Mayer Lehman, and their descendants, comprise the “single family.”

I didn’t know a thing about the brothers. (Did you?)

What I am sure we all knew was that Lehman Brothers went bust on September 15, 2008 after being operational for 158 years, and it was the largest bankruptcy in history.

The public credited the failure as the seminal event that literally pushed capitalism to the brink.

In reality, even though the downfall greatly intensified the 2008 financial crisis and Americans lost an estimated average of more than a quarter of their collective net worth, the disaster was primarily caused by deregulation in the financial industry.

Nevertheless, the name “Lehman” became –and remains - synonymous with Wall Street hubris at its very worst.

“The Lehman Trilogy” begins and ends with the debacle, yet devotes little stage time to it.

The “story of Western Capitalism” turns out to be a history play that outlines the story of the original three Lehman brothers; their sons Philip and Herbert, inheritors of the firm; and finally, grandson Bobbie who ran the global giant into the ground.

Twenty-three--year-old Hayum Lehmann’s arrival in New York from Bavaria in 1844 (immigration changes his name to Henry Lehman) launches the play; younger starting brothers, Emanuel (ne Mendel) and Mayer, follow over the next six years.

Over the course of 164 years, three generations of Lehmans navigate their way from humble beginnings to the creation and operation of a major financial institution positioned at the heart of the world economy.

Upon arriving in America, Henry, the son of a Bavarian cattle merchant, brims with astonishment, trepidation and a sense of infinite possibilities.

He says of himself: “He took a deep breath and walking quickly, despite not knowing where to go, like so many others he stepped into the magical music box called America.”

The brothers start out as storekeepers in Montgomery, Alabama, where they sell cloth by the inch and basic home goods to poor Southerners.

Blessed with tenacity and good luck, successively – and successfully – they keep reinventing themselves, creating a primitive credit system, inventing the concept of “middleman,” and evolving into a lending bank, then an investment bank and finally a trading house.

Their core commodity slowly becomes money and their firm Lehman Brothers makes a specialty of monetizing catastrophes, including burned-down plantations, world wars, the Wall Street crash, nuclear tensions.

Within the magical music box of America, Lehman Brothers fulfills the potential of the American Dream by financing the railroads; the Panama Canal; Ford cars; oil wells; Sears, Roebuck & Co.; cigarettes; Pan American Airways; movies that include blockbusters “King Kong” and “Gone with the Wind”; the rise of television; computing; and weaponry.

“The Lehman Trilogy” is a vastly entertaining (and superficial) look at the initiative, ambition and insatiable hunger for money that built modern capitalism. At the same time, the multigenerational story of expansion, acquisition and loss skirts the corruption, hubris and rapacious greed that destroys its own creation and almost takes the world with it in 2008.

It’s up to the audience to decide whether what they have witnessed is business as usual or the unacceptable face of capitalism.

“The Lehman Trilogy” started life in 2013 as a radio play by Italian dramatist and essayist Stefano Massini who later adapted his script into a five-hour stage version.

In 2015, British Olivier-and Academy Award-winning director Sam Mendes discovered the play at The Piccolo in Milan. Subsequently, he took a strong hand in the creation of an English language version that he planned to direct for the National Theatre.

National Theatre associate director Ben Power is responsible for the creation of the current three-hour English language version.

Power wisely chooses to treat the real-life chronicle as if a novel. The characters describe their characters, their settings and their histories in the third person with only occasional dialogue, and somehow the writing is so fluid and vibrant, the approach works.

And that is not the first surprise.

Sam Mendes may be the first in memory to rely on ceaselessly inventive and surprising minimalist elements in order to create an epic theatrical experience.

Talk about outrageous decisions. Mendes cast a mere three actors to portray everybody who puts in an appearance during the 156-year saga, including the brothers, their descendants, spouses, colleagues, rivals and employees..

Two-time Olivier award-winner Simon Russell Beale, Ben Miles (Captain Peter Townsend in “The Crown”) and three-time Olivier nominee Adam Godley take up the challenge.

Carrying forth in the tradition of Britain’s most notable story-theater production, the Royal Shakespeare Company’s fabled “Nicholas Nickleby,” the trio delivers a stunning display of skill, dexterity, imagination and endurance.

Just to give you a notion of what they are up to, Adam Godley portrays 42 characters, counting one character at various ages.

Russell Beale is first seen as Henry Lehman, Miles as Emanuel, and Godley as Mayer.

They wear black mid-19th-century frock coats (Katrina Lindsay of “Harry Potter (and the Cursed Child” is the costume designer) and never change out of them as they tell the story and deliver brief, sharp impersonations as they metamorphose from one character to another.

Though the original siblings are long dead before the play ends, they remain on stage, functioning as guides and observers.

Simon Russell Beale and Miss Liberty

Simon Russell Beale and Miss Liberty

Russell Beale is a touching Henry Lehman, who sadly succumbs to yellow fever at the age of 33; Emanuel’s son, ruthless capitalist sharp shooter Philip Lehman; a demure 19th-century Southern miss; a libidinous 20th-century divorcée who marries into the clan, only to regret it; a two-year-old child; a centenarian rabbi, and (believe this) a slave, slave-owner and the governor of Alabama.

Miles is an imposing Emanuel Lehman; Mayer’s son Herbert, who "wanted things to be fair” and ended up a liberal politician with a second career as governor of New York; and Lewis Glucksman, the tough-guy trader whose fierce battle for control of Lehman Brothers in 1983 was a curtain-raiser for the titanic struggles of ego and that swept Wall Street over the next decade.

Godley creates an earnest Mayer Lehman, the youngest of the three brothers, the last member of the family to helm the firm, Philip’s elderly son Bobbie, whose creepy dance that he performs to mark the company’s precipitous expansion causes his death; and eight women who are rival potential wives for Russell Beale’s Philip Lehman.

There’s no denying it’s a stunt, and it’s such a dazzling and dexterous stunt you feel ashamed to wonder what it would have been like had there been more drama and conflict for the actors to chew over.

Es Devlin’s set provides another dose of astonishment.

Her superlative eye candy is made up of a huge, gleaming 800-square-foot transparent glass cube (nine panes weighing between 750 and 1,000 pounds were used in its construction) mounted on a turntable, and surrounded by a black background and an enormous curved cyclorama on which are projected splendid, often startling, mostly black-and-white video images designed by Luke Halls.

Devlin’s cube is divided into quadrants with three small interconnecting spaces and a much larger antiseptic twenty-first-century board room.

The effect is that of a single floor of a corporate skyscraper floating in space.

The cube revolves almost continuously as unobtrusive pianist Candida Caldicot accompanies the action playing mood-setting music by Nick Powell.

Huge gasp inducing images surround the cube. We see waves, flames, cotton fields, clouds, the Statue of Liberty stranded in the middle of the ocean; stock market boards that move, faster and faster, until they are nothing but a blur; a cotton field that suddenly sprouts a nightmarish Industrial Revolution factory.

The New York skyline morphs, bit by bit, over a century-and-a-half from a small collection of pre-Civil War warehouses to a stunning view of contemporary Manhattan at night.

Every generation of the family is plagued by prophetic nightmares (of stacks of coins wobbling as they get higher, roofs of houses caving in) and color is utilized strictly in these unnerving videos.

When Bobbie Lehman dies in 1969, he leaves no heirs. For the first time, the firm is not led by a Lehman.

In the third act, which is the weakest, risk-taking traders operate in a deregulated market – with disastrous consequences. As the end approaches the visuals blur and the office spins at a dizzying pace. Fifteen of the firm’s employees gather and wait hear of the company’s closing. The telephone rings and the play is over.

“The Lehman Trilogy” is mammoth, dazzling, and filled with flair and energy. The actors, design team and director are brilliant. But entertaining us doesn’t seem to me to be enough.

Shouldn’t we at least the very least be unsettled by the Lehmans and their legacy and the brand of capitalism they practiced and inspired?

Simon Russell Beale, Adam Godley, Ben Miles

Simon Russell Beale, Adam Godley, Ben Miles

More information: Park Avenue Armory

Henry Edwards | Comments Off |

Henry Edwards | Comments Off |