‘AMY AND THE ORPHANS’ IS A THEATRICAL FIRST

Tuesday, May 22, 2018 at 8:36PM

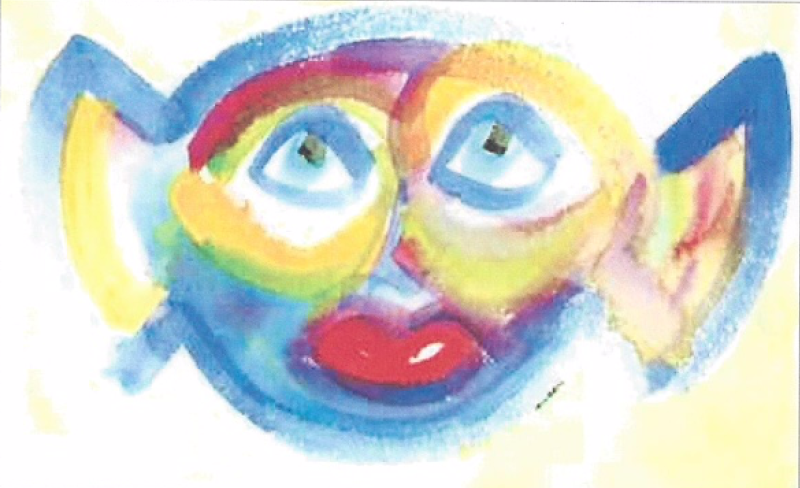

Tuesday, May 22, 2018 at 8:36PM  Vanessa Aspillaga, Jamie Brewer, Debra Monk and Mark Blum (photo by Joan Marcus)

Vanessa Aspillaga, Jamie Brewer, Debra Monk and Mark Blum (photo by Joan Marcus)

HENRY EDWARDS - NEW YORK - March 9, 2018

Until Lisa Ferrentino’s family comedy-drama, “Amy and the Orphans,” arrived at Roundabout’s Laura Pels Theatre, there’s never been an Off Broadway or Broadway production to cast an actor with Down syndrome in a lead role.

Groundbreaker Jamie Brewer, 33, has been performing since the eighth grade and is best known as Adelaide 'Addie' Langdon on FX’s “American Horror Story.”

The actress portrays the Amy of “Amy and the Orphans.” Amy has Down syndrome, lives in a group home in Queens, has a boyfriend, loves movies, manages a movie theatre and punctuates her conversation with quotations from her favorite films (“Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”).

Before I go any further, let it be said that Brewer is superb and her performance is one of most entrancing in quite some time.

Theatergoers know playwright Ferrentino from her 2015 debut, “Ugly Lies the Bone.” The agonizing portrait of a badly disfigured American veteran of the war in Afghanistan scored a critical and commercial success for Roundabout Theatre Company, encouraging the organization to commission the play that became “Amy and the Orphans.”

Ferrentino bases the character of on her deceased aunt, Amy Jacobs, who was born with Down syndrome in 1964.It was a time when children with the condition were called Mongolian idiots and hidden from view. Ferrentino’s grandparents were advised not to take the baby home, did as they were told, and Jacobs spent most of her life in state-funded institutions where she never learned to read. Ferrentino’s script includes the instruction: "Finding a talented actor with Down syndrome isn't difficult, so please do it.”

Eight-time Tony nominee Scott Ellis (“The Elephant Man”; “She Loves Me”) directs the production and the intentions of everyone involved are so worthy it would be a pleasure to report that the result is wonderful.

Unfortunately, “Amy and the Orphans” turns out to be a mixed blessing.

Fearful perhaps of the subject, the play goes out of its way to be too audience friendly with Ferrentino dishing up doses of hoary comedy (some of it really funny in spite of itself) that suggests very early Neil Simon.  Josh McDermitt and Jamie Brewer (photo by Joan Marcus)

Josh McDermitt and Jamie Brewer (photo by Joan Marcus)

“Amy and the Orphans” takes place in two time zones, the 1960s and the present and the Sixties come first.

Sarah (Diane Davis) and Bobby (Josh McDermitt from “The Walking Dead”) are married and in their mid-thirties, and have checked into a couples-therapy retreat. They are caught up performing a silly New Age exercise about trust and personal truths that inevitably turns into a not-all-that serious squabble.

Fast-forwarding to the present day, we next meet Amy’s two older siblings, the “orphans” of the title, Jacob (Mark Blum) and Maggie (Debra Monk).

They have flown to New York, he from California (it was the farthest he could escape from his Long Island roots) and she from Chicago, to visit Amy at the state residence in Queens, NY, where she lives, inform her of their father’s death and transport her to Montauk, at the far end of Long Island, for their father’s funeral.

Jacob and Mary, who are both in their sixties, are so exaggerated, loud and aggressively neurotic, they seem to have escaped from a Borscht Belt that doesn’t exist anymore.

Jacob, a classic kvetch, maintains a strict organic diet (he juices six times a day), is a practicing Born Again Christian, and recently had braces placed on his teeth (“because of a serious jaw misalignment").

It’s no surprise that he paid tribute to Jesus during their mother’s Jewish funeral service (which neither sibling bothered to tell Amy about).

Maggie, a real estate agent from Chicago, is a shrill, pushy, full time mess. She comes equipped with a theme song that she bellows repeatedly and goes like this: “Isn’t there a grown-up who can take care of this for us? We’re orphans now!”

Amy’s devoted, capable, pregnant, foul mouthed and very loud caretaker Kathy (Vanessa Aspillaga) is mandated by regulations to accompany Amy, a ward of the state, on the road trip down the Long Island Expressway to the funeral. The pushy “walking embodiment of Long Island” insists on driving.

Road trips are nothing new — think of the riotous, dysfunctional, car-bound family journey in “Little Miss Sunshine.” But this particular version is studded with clichés: carsickness (Maggie), whining (Jacob), and disapproval (Kathy).

What proves of interest is the interaction between Amy and her siblings.

Even though they have visited their institutionalized sister on holidays, it turns out Jacob and Maggie have largely ignored her and Amy is little better than a stranger to them. Nor do they know what to make of the mix of jokes and movie quotations that is part and parcel of Amy’s conversation, and do not listen.

As the ride goes forward, Kathy leads Jacob and Maggie to the realization that Amy is more self-aware than they realized, and that they have neglected her.

Blum and Monk are old pros and Aspillaga is shamelessly funny as the actors navigate their way in, out and around the melodrama and sentimentality that punctuate their unlikely journey.

Meanwhile, the roots of Amy’s neglect are gradually revealed in the series of flashbacks to the 1960s that occur along the way.  Jamie Brewer as the play’s title character, with (in front seat) Vanessa Aspillaga as her caregiver and (in back seat) Debra Monk and Mark Blum as her siblings.

Jamie Brewer as the play’s title character, with (in front seat) Vanessa Aspillaga as her caregiver and (in back seat) Debra Monk and Mark Blum as her siblings.

We’ve encountered Sarah and Bobby in a couples retreat. Now we learn that Sarah has just given birth and is suffering from depression.

Bobby, perpetually horny, and thinks that sex will solve his wife’s problems. But Sarah is repelled by her husband’s chronic overeating, and it’s not a pretty sight for her or the audience when he takes off his shirt. (It’s another example of what is supposed to be funny but isn’t.)

Eventually, it becomes clear that Sarah and Bobby, both deceased, were the parents of Jacob, Maggie and Amy, and were struggling with trying to determine whether they were capable of caring for an infant daughter with Down syndrome without destroying the rest of their family.

“Our daughter's name means love. But that's not why we picked it. We picked it 'cause it was the shortest in that book of names. So even though the doctors told us she'll never learn to spell or write, if it was only three letters we said we'd try,” Bobby tells his wife before delivering the ultimatum that trying has proved to be impossible, and that Amy must be institutionalized.

As they reach the end of the road and Bobby’s funeral awaits them, Kathy, the ultimate truth teller, delivers a shocking revelation about Amy's past.

Maggie and Jacob’s vaguely recall Amy’s childhood in a state institution as pleasant— after all their family would take her to the movies every few months.

Kathy sets them straight. Amy was confined in Willowbrook, the hideous Staten Island institution for mentally ill or delayed children that functioned as a “human warehouse” and shut down in 1987.

Willowbrook was filled to more than double its capacity. But crowding was the least of the horrors. Some residents were reportedly used as test cases for hepatitis studies. Others were left to languish, abused and living in squalor with little medical or mental health care.

In truth, Amy’s younger years were years of ongoing suffering.

The information is such an authentic shocker, but that doesn’t mean the laughter is completely shut down.

Funniest of all (and it really is funny), Maggie stages an uproarious memorial service for her deceased father in a jammed-to-the- rafters Chinese restaurant and (for those who think they’ve seen everything, she utilizes a karaoke machine to deliver her eulogy.

Drawing the play to a conclusion, Amy steps in front of a red velour curtain and delivers a breathtaking monologue comprised of classic lines from the movies she has seen over the years. It’s funny and emotionally wrenching, and a spellbinding tour de force for Brewer.

“I coulda been a contender. I coulda been somebody,” she says with absolute conviction, rousing cheers.

And Amy probably could have been had she not been born in a time when the options for treatment were so limited and cruel.

Mixed blessing or not, “Amy and the Orphans” leaves audiences happy and enlightened.

It’s a safe bet, thanks to Ferrentino, they will never think about people with Down syndrome in precisely the same way again.

For more information about the show, and Roundabout’s busy new season visit : Roundabout Theater