‘PARADISE BLUE”- SELLING OUT COMES WITH A PRICE

Monday, May 28, 2018 at 3:43PM

Monday, May 28, 2018 at 3:43PM

Kristolyn Lloyd and J. Alphonse Nicholson are not having a happy moment.

Kristolyn Lloyd and J. Alphonse Nicholson are not having a happy moment.

HENRY EDWARDS - New York - May 19, 2018

“One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn't going to go off. It's wrong to make promises you don't mean to keep," Chekhov said famously.

Dominique Morisseau’s “Paradise Blue” at Signature Center’s Linney Courtyard Theatre jumps the gun on the great playwright.

When the lights come up, we see a trumpeter lift his instrument to his mouth and begin to play when a gunshot suddenly goes off. We don’t know who fired the weapon or ; nor do who got shot. And let’s not think about motive. And since the play is structured as a flashback, we’re not going to obtain any answers until the two-act play draws to a conclusion.

By then, Obie and Steinberg Playwright Award winner Morisseau has utilized so many different styles and introduced so many ideas, you may not recall the mysterious shooting that occurred two-and-a-half hours ago.

Either way, the identity of the assailant and the victim are so surprising and unlikely, you will leave the theatre bewildered, astonished, or both.

Morisseau, a native of Detroit, cites August Wilson as the inspiration for her trilogy, “The Detroit Project.”

Wilson was a native son of Pittsburgh and his brilliant ten-play Pittsburgh Cycle chronicles the broad African-American experience by placing each (except one) of his efforts in Pittsburgh during a different decade of the 20th century.

Morisseau’s “The Detroit Project” sets each of her three plays in Motor City during a different decade.

“Detroit ’67” takes place during five July days of the infamous 1967 Detroit riots; “Skeleton Crew” is set in the break room of Detroit’s last exporting auto factory in 2008 at the height of the Great Recession.

“Paradise Blue,” the second in the series, is making its New York debut after a 2015 world premiere at the Williamstown Theatre Festival.

The production launches the playwright’s Signature Residency, providing her with three premieres over the next five years.

“Paradise Blue” is set in 1949 in the Paradise Club, a shabby bar and jazz club with an upstairs rooming house located on the downtown strip Paradise Valley in the small African-American community of Black Bottom.

Once known as Detroit’s Harlem, Paradise Valley played host to music icons like Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald in the 1940s.

In 1949, the club, indeed all of Black Bottom, is in danger of extinction as incoming mayor Albert Cobo is a bigot with plans to bulldoze and then gentrify the neighborhood. Not only will the results force residents from their homes but also destroy the location as a haven for African-Americans.

Trumpeter/composer/arranger Kenny Rampton's original and swinging jazz score leads off both acts and both his music and the grungy look of Neil Patel’s stage design suggest the moody, dark and dramatic trappings of film noir. But femmes fatales, hard-boiled gumshoes and antiheroes fated to die are not exactly what you get at the outset.

The Paradise Club clearly has seen better days, and Rui Rita’s lighting is so dim, you will have to squint. We will also able to make out a large overhead sign running from one side to the other ringed with electric bulbs that shout PARADISE.

Like his father before him, Blue (a super intense J. Alphonse Nicholson), is a trumpet player and the owner of the faded club. The musician fronts a quartet whose sidemen include the drummer P-Sam (smooth, self-confident, hot headed Francois Battiste) and piano player Corn (gentle giant Keith Randolph Smith), an overweight, middle-aged widower pining for his deceased wife.

To Sam’s dismay, the temperamental Blue has recently fired the band’s bassist, reducing the Black Bottom Quartet to an unemployed trio.

Sam’s got it right. Blue is a real piece of work, difficult, proud, impatient, moody, insecure and inflexible, and a terrific player.

Corn, a major conciliator, blames racism for Blue’s problematical personality. “Blue ain’t a bad man,” he volunteers. “He just wanna be mighty but the world keep him small. Cost of bein’ colored and gifted. Brilliant and second class. Make you insane.”

It may just be Corn’s conjecture, but in reality, Blue is trapped in the grip of haunting memories of his ill-fated mother and psychotic father and the awful end of their lives. As a result, the trumpeter is slowly losing his talent and his mind.

Audiences expect the jazz artists that inhabit stories about them to cause one problem after another in their pursuit of artistic and personal freedom.

Think “Bird,” “Mo’ Better Blues,” “Sweet and Lowdown” and "Round Midnight.”

In each case, your sympathy for the troubled artist never falters. But Blue is so temperamental and harsh, it’s not long before you stop caring about him.

The drummer’s got it right, Blue is a real piece of work: difficult, proud, impatient, moody, insecure, and inflexible, but he can also wail.

“Blue ain’t a bad man,” sighs Corn excusing Blue’s difficult personality as the price a black artist pays in a racist society. “He just wanna be mighty but the world keep him small. Cost of bein’ colored and gifted. Brilliant and second class. Make you insane.”

But Blue turns out increasingly to be in the grip of haunting memories of his ill-fated mother and psychotic father, and as it turns out, as a result of mental illness, he is slowly losing his talent along with mind.

Audiences expect the jazz artists that inhabit stories about them to cause one problem after another in their pursuit of artistic and personal freedom.

Think “Bird,” “Mo’ Better Blues,” “Sweet and Lowdown” and "Round Midnight.”

In those cases, your sympathy for the troubled artist never falters. But Blue is so temperamental and harsh, it becomes hard to care about him.

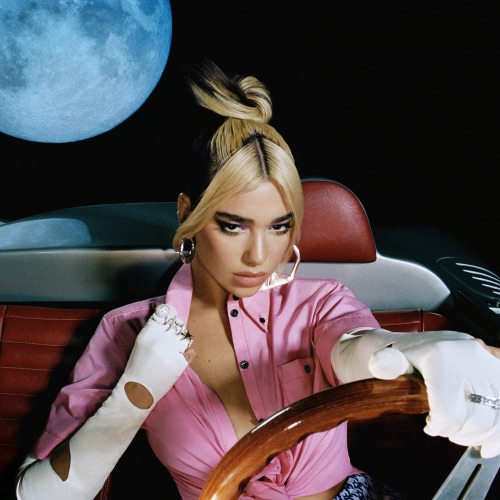

It’s especially unnerving to take in his harsh, short tempered and domineering treatment of his girlfriend, shy and super-wholesome Pumpkin (a splendid Kristolyn Lloyd). If ever there was an archetypical good girl, this one is it.

Her life is exclusively devoted to pleasing Blue, whom she loves and thinks is a genius (which in certain ways he is), eagerly functioning as his housecleaner, cook, waitress and lover.

When no one’s looking, she reads aloud from a book of poems by the relatively unknown Harlem Renaissance writer Georgia Douglas Johnson,

“The heart of a woman goes forth with the dawn,” Pumpkin muses out loud.

Her behavior is an intriguing eccentricity, but so far nothing about Blue and Pumpkin feels truthful enough to be compelling.

Half way through the first act, Silver (a fearless Simone Missick) shows up, bringing a much needed dose of heat with her.

Talk about film noir. She is dressed all in black and has the slow-motion hip swaying walk of a black panther. Silver hails from Louisiana, she’s a widow with a suspiciously dead husband and she wants to rent a room, flashing the large wad of cash stashed in her plunging neckline to pay for it.

Blue begrudgingly complies and labels her the “black widow.”

Silver and Pumpkin are a study in opposites, and the meek Pumpkin grows increasingly fascinated by the worldly newcomer’s sophistication and sexual aggressiveness.

In one delicious sequence, while changing the linens in Silver’s upstairs room, Pumpkin pulls the boarder’s black bustier out of a drawer, tries it on over her cardigan, and pretends to walk like a “spider woman” in front of an invisible mirror.

In another, to her great shock, she discovers a gun in Silver’s luggage, reinforcing the rumor that the guest shot her husband to death.

It doesn’t take long before the temptress seduces Corn, dulling the flame he had still carried for his late wife. Silver also takes an active interest in the economics of the Paradise Club.

Viewing Black Bottom is an opportunity for black people to run their own enterprises rather than “sharecroppin’ and reapin’ white folks’ harvest,” she makes no bones about having sufficient cash to buy the club.

But Blue wants no part of her.

Morisseau utilizes colloquial black dialect to create poetically stylized dialogue and Battiste and Smith are masters of delivering it with impressive naturalness.

What’s on their minds is gentrification, and they fear Blue is going to receive an offer to sell the club to the racist establishment and be tempted accept it.

P-Sam is even convinced Blue will sell them out, but Blue blows off their concerns.

However, when he is alone with Pumpkin, he feverishly confesses that an offer has been placed on the table and that he plans to accept it. Pleading hysterically with her, he insists that they must abandon the past and move to Chicago if he is to regain his talent.

Pumpkin views Black Bottom is an oasis from the harsh and biased outside world, has always lived there, loves it and doesn’t want to leave. Yet she is compelled to accede to her lover’s wishes.

When the numbers-playing Sam wins a lot of money, and he and Silver come up with their own plan to buy the club, “Paradise Blue” takes another drastic shift and transforms into shameless out-and-out melodrama dosed with surrealism.

There’s an astonishing nightmare scene in which the tormented Blue, whose musical gifts have evaporated, is tortured by the sounds of trumpet music that literally seems to attacking him. (Sound designer Darron L. West does fabulous work).

Mistaking the meaning of an embrace between Pumpkin and Sam, Blue attacks his loyal girlfriend with so ferocity, it’s clear she’s in danger.

Ultimately, Silver comes to her rescue and the two women have a remarkable exchange.

Pumpkin listens intently as Silver makes the point that she must stop being docile and thinking easing a man’s troubles will make her safe. No woman is ever safe, continues the toughened voice of experience, and there’s another way of walking through life. With that Silver hands over her gun and teaches Pumpkin how to use it.

In the next scene, Pumpkin has hed her cardigan for a red satin gown and has obviously become Siver's disciple.

Corn and Sam have learned Blue has secretly decided to sell the Paradise to the city for $10,000, beating to the bunch before they made their offer.

That Blue is willing to deliver their spiritual home and livelihood into the hands of “no count crackers that think of me as less than the spilled whiskey on they shoe” triggers a ferocious physical assault. In order to bring an end to the violence, Pumpkin emerges with the gun.

“Every part of this place is who I am,” she tells Blue, speaking of her home in Black Bottom. “It’s killin’ you but it’s keepin’ the rest of us alive.”

Pumpkin’s action is both self-defense and a kind of divine mercy and transforms Blue into a film noir who is meant to die.

Director Ruben Santiago-Hudson runs with the stylization in this production allowing it to take its perplexing course without intervention.

Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing,” the 2011 Pulitzer Prize-winning “Clybourne Park,” set in the same fictional Chicago neighborhood as Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play. “A Raisin in the Sun.” and August Wilson’s glorious “Jitney” all dealt with gentrification.

In those cases, no emotional and moral focus was given to those who are committed to staying. Nor did anyone get shot.

Morisseau and her play seem in awe of their lack of control.

'Paradise Blue' has been extended to June 17 at Signature Center (ticketservices@signaturetheatre).

. Kristolyn Young Man With a Horn: J.Alphonse Nicholson

Kristolyn Young Man With a Horn: J.Alphonse Nicholson

Study in Contrasts:Simone Missick, Kristolyn Lloyd

Study in Contrasts:Simone Missick, Kristolyn Lloyd