‘MLIMA’S TALE’ IS ALL ABOUT GREED

Sunday, June 3, 2018 at 8:06PM

Sunday, June 3, 2018 at 8:06PM

Sahr Ngaujah with Jojo Gonzalez and Ito Aghayere in silhouette behind him (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Sahr Ngaujah with Jojo Gonzalez and Ito Aghayere in silhouette behind him (Photo: Joan Marcus)

HENRY EDWARDS - New York - May 12, 2018

It’s been said Lynn Nottage isn’t on a mission to save the world, but as a sensitive and engaged citizen and human being, occasionally she believes one of the world’s myriad problems cries out for action—and, since she’s a playwright, that usually means writing a play.

Two of those efforts, “Ruined” (2009) and “Sweat” (2017), received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama; Nottage is the first woman to win this award twice.

“Ruined,” a dramatization of the plight of women in the civil war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo, conveyed the agonizing message that rape is a profoundly damaging weapon of war and must be stopped.

“Sweat,” the first theatrical landmark of the Trump era and a portrait of the America that had come undone, dramatized the disaffection and racism of white working-class voters in the rust belt of Pennsylvania.

“Mlima’s Tale,” Nottage’s new play at The Public’s Martinson Hall, chooses as its subject one of the largest, most shadowy criminal trafficking networks in the world, the $10 billion a-year ivory poaching trade.

That one elephant is killed every 15 minutes is all you need to know to appreciate Nottage’s concern.

If her play was documentary drama, one of those elephants undoubtedly would have been title character, Mlima ("mountain” in Swahili), a decades-old Kenyan bull elephant and "one of the last of the big tuskers.” Each tusk was 10 feet long and weighed 198 pounds.

Around 25 elephants currently exist that are genetically disposed to grow tusks so big they sometimes reach the ground.

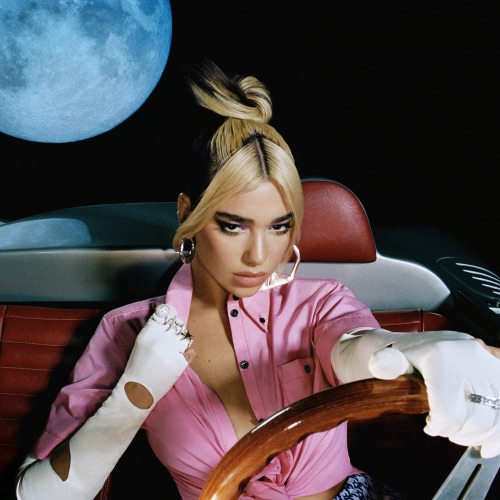

Actor and director Sahr Ngaujah, who is of Sierra Leonean ancestry, portrays Mlima. Ngaujah is perhaps best known to New York audiences for playing another title role, that of the late Nigerian singer Fela Kuti in the musical “Fela!”

Bristling with intensity and remarkable athleticism, he delivers a majestic performance that effortlessly captures the physical, emotional and spiritual grandeur of the mighty animal. Ngaujah is such an arresting visual presence you can't take your eyes off him.

Mlima lives in the savannas of a Kenyan game preserve and supposedly under the protection of national laws.

Our first sight of him finds him bathed in moonlight, an imposing silhouette against the bright night sky.

In his opening monologue—it will turn out to be Mlima’s last living words—the elephant utilizes rich, sensory language to tell us “how you listen can mean the difference between life and death. It’s the truth of the savanna, something we all learn at a very young age.”

That ability has proved incapable of sparing him.

Poachers have shot Mlima with a poison arrow (poachers inside parks often use arrows instead of rifles in order not to alert rangers) and his will to live has enabled him to run from them for 40 days. But he is weaker and they are closing in.

Mlima’s anguished wail shakes the theatre during the agonizing death scene that precedes the poachers hacking off his tusks.

Nottage’s “Ruined” is an adaptation of Brecht’s “Mother Courage and Her Children.” For “Mlima’s Tale,” the playwright chose the format of Austrian writer Arthur Schnitzler’s once controversial 1897 play, “La Ronde,” as her model.

“La Ronde” (film buffs may recall Max Ophüls’s stylish 1950 film version) presents sex as a daisy chain of ten erotic encounters, each a duet in which one character from each scene becomes a part of the next.

Utilizing the same prototype of overlapping lives, “Mlima’s Tale” traces the step by step journey of the fallen elephant’s mammoth tusks as they depart Kenya, travel through several countries while undergoing an increasingly profitable and slimy series of transactions before they reach their final destination in a Beijing penthouse.

Actors Kevin Mambo, Jojo Gonzalez and Ito Aghayere dexterously (and quickly) bring to life twelve participants in the revolving door of a market economy powered by greed and riddled with corruption, deceit and complicity.

The enormously skilled trio relies on restrained changes of body language and accents, a touch of exaggeration and Jennifer Moeller’s costumes to create a gallery of poachers, park warden, police chief, African government official, Chinese collector, Vietnamese smuggler, boat captain, master ivory carver and nouveau riche millionairess art buyer, among others.

In the act of doing business, each character undercuts the one before and lies to the next on the ladder up. Along the way, there are betrayals or pay offs or both.

One person is always in control and one person struggling to gain control. At some point each has the option of not participating but ultimately chooses to participate.

Several times, characters ask for assurances that the ivory was extracted legally, that no animals were really harmed, and that anyone who does harm animals will be punished.

No matter their individual concerns, each ultimately lacks sufficient integrity, allowing greed, moral weakness and self-preservation always to win the day.

Nottage creates these duets with restraint. Unbridled capitalism and not its wheelers and dealers, each with an understandable (but often infuriating) motive, is the real villain here. Capitalism simply does not allow virtuous behavior or anything resembling it.

As with Brecht, we always know who the winner is going to be and around the midpoint, “Mlima’s Tale” turns wearisome and didactic.

The subject of poaching is nothing new, we share the playwright’s anger about it, and each day’s news about our federal government destroys the shock value of greed and corruption.

What does continue to fascinate is Nottage’s treatment of Mlima after the elephant’s death.

The Maasai believe that if you don’t give an elephant a proper burial, the elephant will haunt you forever. The conviction transforms “Mlima’s Tale” into a ghost story about a murder and the victim’s afterlife.

After the death of the animal, Ngaujah performs a stark, otherworldly dance-like ritual and covers his face and torso with streaks of white paint to represent Mlima’s transformation from regal elephant in life to commodity in death.

While Mlima's body has been deserted, his spirit remains with his tusks.

During every scene that follows, the spirit stands silently and imposingly in the background, observing and listening intently to the negotiations. Ngaujah smears each of the participants with white paint at exactly the moment the transaction has been completed. The stains are well earned marks of Cain.

During a voyage from the Kenyan port city of Mombasa to Vietnam, the tusks are placed in the cargo hold of a ship. The sight of a partially clad and caged black man inevitably summons thoughts of the Middle Passage, the stage of the slave trade in which millions of Africans were abducted into slavery and shipped to the New World.

Again, self-interest and greed are the order of the day.

Jo Bonney (“An Ordinary Muslim,” “Red Letter Plays: Fucking A”, “Cost of Living”) is a director with an artistic flexibility that allows her to transform a multitude of styles into coherent and satisfying theatrical works. In the case of “Mlima’s Tale,” her theatrical inventiveness and discipline have been applied to create a show that is speedy, spare and beautiful to look at.

Riccardo Hernandez’s minimalist set consists mostly of an empty box and utilizes a series of sliding panels that fly open and close to reveal multitudinous locations. No two scenes occur in the same place and each scene is “titled” with an appropriate (sometimes silly) African proverb (“No one tests the depth of the river with both feet") projected on graceful floating screens.

Lap Chi Chu’s richly colored lights make an immense contribution to the spare but arresting stage pictures.

Musician and composer Justin Hicks, visible throughout the performance just outside the stage proper, makes an extraordinary contribution.

Hicks and the sound designer Darron L West miraculously craft a world where “thunder is not yet rain.” We hear animals breathing, insects whirring, and an elephant’s trumpeting roar that shakes the theatre.

In a final speech, Mlima tells the audience, “If you can hear me, don’t come to mourn me,” he tells us, warning the members of his tribe to protect themselves. “Run! Run! RUN!”

The poachers who killed Mlima were offered $500, but were paid half. Ultimately, the tusks fetched a staggering $1.1 million in China.

The agonizing last image of the play takes us a penthouse in China whose owners are delighted to show their newest status symbol, an exquisite ivory set. The lights come down on Ngaujah who has ended up a decorative carving.

Nottage’s passion is so overwhelming it makes it easy to forgive the monotony that takes over the central portion of the play.

Sahr Ngaujah (Photo: Joan Marcus)

Sahr Ngaujah (Photo: Joan Marcus)